SYNOPSIS

The film reveals the mechanism that entices human beings to voluntarily turn themselves into submissive, faceless creatures. Thus, they become a resource to be used by the state – a grey lump of ore oblivious to the innate value of their individual life.

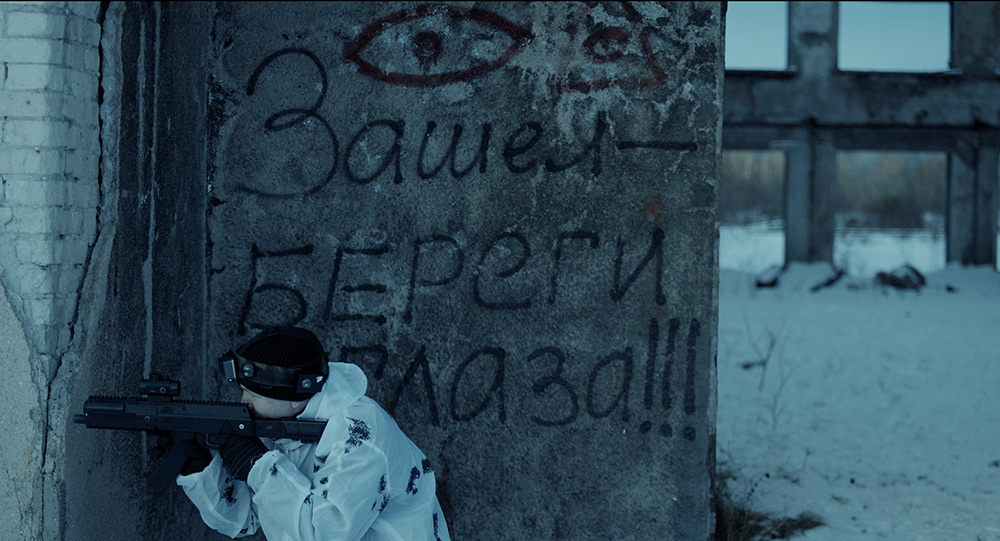

The town of Apatity first came into being as a concentration camp. Today, 50 years is considered a ripe old age in the industrial town of Apatity, while the environment is at the brink of an ecological disaster. The adults while away their lives at the factory bus stop whilst the children – the token of their immortality – miss out on family life and warmth. Instead, they are left in the care of state structures that inculcate in them the traits of prisoners, making use of celebration-like dancing and marching trainings. Neither the children nor their educators are aware of this. They are convinced that they are bringing up a generation of patriotic heroes, fated to become legionnaires of the Earth and the adjacent cosmic expanses. The only way out of this system is death. However, if you die for the state you become an immortal hero.

The dancing and marching fall into the conveyor-belt rhythm of the moving trains, full of grey lumps of ore that are also destined for immortality: they will become phosphorus fertiliser on which new life will grow.

GENRE: creative documentary

CATEGORIES: human rights, state structures, propaganda, industry, children

IMMORTAL TRAILER

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

My previous films were about unique places and people with strong personality and had no direct connection to my own biography. I enjoy exploring the world through the camera lens, observing events and people’s behaviour a little from the side. “The Immortal” is my first work, which has something to do with my childhood and teenage experiences in post-Soviet Russia, a place with its own rules that a young person took for granted rather than questioned.

One of the objectives behind creating the Declaration of Human Rights was to protect people from slavery. It was motivated by the tragic experience of the Second World War when human life had been devalued to a statistical unit. Who could have imagined 70 years ago that slavery can be voluntary? In the USSR, a powerful propagandistic structure was created, based on the sense of belonging to a community and unconditional acceptance of authority that is typical for a patriarchal society and perpetuated in modern Russia. The foundation of this structure is the idea of gaining immortality through sacrificial service to the interests of the state. Immortality is a candy for which the totalitarian state, with its economy based on the exploitation of natural resources, buys a person’s will, strength, talent, and lifetime, turning the human being into another resource, faceless as a grey lump of ore.

Perhaps they have died already… but the imaginary glory of being an “immortal hero” veils the reality. The race for survival in the labour camp-like living conditions kills them slowly and takes from them their future: their own children. We come to this world absolutely free, and our will is an incredible force capable of changing the reality. However, it can easily be manipulated by restricting resources and depriving people of the most powerful protection: a loving family. This is how the mechanism of voluntary slavery, carried on by generation after generation, enables irresponsible exploitation of natural resources and enrichment of the elites.

IN CONVERSATION WITH THE DIRECTOR KSENIA OKHAPKINA

Why Apatity? Is this settlement in the north-west of Russia outstanding in some way?

Or did the place represent a phenomenon, a wider issue you wanted to highlight?

This place is very typical for Russia. There are hundreds of such towns, former labour camps and military bases. Some of them have numbers instead of names. Apatity as well as other such towns are a soviet phenomenon. They are the backstage of the soviet empire, built on propaganda and the labour of prisoners. I chose Apatity because there was no settlement there before labour camps were established and railroads built in the 1930s to mine and deliver ore. The town was named after the ore minerals, apatites.

Apatity has no national or cultural background since the prisoners were an international community. Therefore, it is a perfect place to explore the soviet way of living as inherited by modern Russia. Moreover, one of the biggest chemical industries in Europe is situated there. Apatity is one of the three towns involved in this industry. These three towns are at the brink of an ecological disaster.

In that sense, this town provides an example of how national economy is built and the elites enriched in Russia. It is a playing ground for mechanisms that steer people to support state power all around Russia.

Your film is very poetic albeit it deals with some existentially heavy topics. There must have been both heart breaking and positive moments during the filming. Can you share some of your highs and lows with us?

What is really breath-taking is the cold beauty of the Khibiny Mountains. It feels like another planet, made of ice and snow. Everything is very powerful there: the night lasts for half a year and the day lasts for half a year. There is absolute darkness but also absolute light. In this place, human life seems so fragile. Especially the life of children.

I felt as if I had arrived in the land of The Snow Queen from Andersen’s fairy tale. The surreal situation of the people I filmed reminded me of the boy Kai from this story who had a splinter of ice in his heart, was bewitched, and fell in love with the cold beauty and power. He collected pieces of ice to spell the word “eternity”.

The only warm-hearted Gerda I found in this strange industrial documentary adaptation of “The Snow Queen” was a dog we met by the factory railroad when filming at night. There is a dog shelter not far from there; another prison-like establishment. The dogs behind the high fence, pulling on their heavy metal chains, bark neurotically, madness in their eyes. From time to time dogs escape from the shelter, although the cost for this is their life – they can hardly find any food in the snow desert expanding outside the shelter.

The dog we met had probably escaped the shelter as well. She was wandering along the empty railroad, shaking of cold. Then she came to us, and when I started to talk to her, she started to bark. However, this barking was not aggressive; it was more like a cry. Her’s was the only sincere story, coming from a warm heart that we were lucky to film. If I did not have this scene, there would be no reason to make this film at all, because the dog is the only free living creature in the film. My poor warm-hearted Gerda!

Probably this film itself is like barking in the darkness. I cannot fight big corporations or state structures with a film. But I hope that there is someone in the darkness of the cinema whose heart will get a bit warmer after seeing it. Otherwise, this Gerda-dog escaped the shelter-prison in vain.

“Immortal” is a very powerful title. What does it mean to you? Is there anything in the world that is immortal?

This film is about time. For me the idea of immortality is something artificial to start with, as it underestimates and devalues the integrity and personality of a moment of time. I feel that everything in the world is very fragile and in constant motion. Even the mountains disappear, they just live longer.

The same goes for human personality: we’re being born and we die every moment because we change all the time. In my point of view, only the process of changing itself is truly immortal. I think that if we appreciated things in their unique integrity and treated every moment as a person, that has absolute value as it will never repeat, we would violate time much less and organise our lifetime and the world around us in a more beautiful and respectful way.

THE FILMMAKERS

Director and writer: Ksenia Okhapkina

Producer: Riho Västrik (VESILIND)

Co-producer: Uldis Cekulis (VFS FILMS)

CREDITS

Cinematographers: Aleksandr Demyanenko,

Artem Ignatov, Ksenia Okhapkina

Co-scriptwriters: Kersti Uibo, Pauls Bankovskis

Composers: Robert Jürjendal, Arian Levin

Sound designer: Aleksandr Dudarev

Film editors: Stijn Deconinck, Ksenia Okhapkina

© VESILIND & VFS, 2019

IMMORTAL PRESS MATERIALS & FILM FACTS

FILM SPECS

Original title: Immortal

Native titles: Surematu (EST),

Nemirstīgie (LAT), Бессмертный (RUS)

Production countries: Estonia, Latvia

Filming location: Russia

Original language: Russian

Subtitles: English

Year: 2019

Length: 61’

Produced by: Vesilind

In co-production with: VFS

CONTACT

Film studio Vesilind (Estonia) / RIHO VÄSTRIK,

producer / vesilind@vesilind.ee / www.vesilind.ee

© 2019 Vesilind. All rights reserved.